Article

Culture is evolving - and that’s a good thing

1st December 2025 by Lee Robertson

If there’s one thing the latest Global Culture Report from the O.C. Tanner Institute makes clear, it’s this: workplace culture…

You feel the bubbling of annoyance in your gut and throat when, having waited ages for a lift in the hotel, and arrived at your room on the 15th floor, your insert the key into the little slot and……nothing! No green light, no satisfying click, nothing. You know that, after a long and tiring day, when all you want to do is flop onto your bed, you’re going to have to trek the whole way back down to reception to get your key reprogrammed. These little moments and others like them, are like mini ‘emotional intelligence’ workouts.

There is, has been for some time and continues to be a lot of talk around the boardrooms and training rooms of the corporate world about the theme of emotional intelligence (EI), something that Mayer and Salovey, some of the first people to try and figure it out, describe as “the capability of individuals to recognise their own emotions and those of others, discern between different feelings and label them appropriately, use emotional information to guide thinking and behaviour, and manage and/or adjust emotions to adapt to environments or achieve one's goal.”

Phew! Not a small ask in anyone’s book!

I’ve given this a lot of thought over the years, having done a lot of training and coaching in the area and in this article which I have entitled, ‘The anatomy of an emotion’ I’m going to try and break it down - parse it, if you will. When I’m training groups on the theme, I always say that the ‘daddy’ or the ‘mother’ of all EI behaviours is self-awareness, and more specifically, emotional self-awareness, that is, knowing what it is that is going on with you at any moment in any time and being able to describe it, explain it and do something useful or helpful with it.

They say there are six main emotional states, namely; anger, fear, shock, sadness, disgust and happiness. Just one positive one, I’m afraid (I’m afraid?). All of the emotions we experience are variations of these. For example, you could ascribe a factor to anger and say

Anger x 1 = mild irritation

Anger x 2 = irritation

Anger x 3 = annoyance

Anger x 4 = frustration

Anger x 5 = anger

Anger x 6 = losing it

Anger x 7 = exploding

Anger x 8 = rage

Anger x 9 = fury

Anger x 10 = apoplexy

And so on. You can use whatever descriptors you like but this is what I came up with on the spur of the moment. This helps us to understand the level to which we are experiencing an emotion and to notice how it might change or move up and down depending on what is happening.

It is also interesting to consider the role of the body on all of this. When I ask people where they experience an emotion, most people indicate that it is in their gut or their chest or their throat. William James, the 19th century philosopher, wrote in his 1884 essay ‘The Heart of William James’ that “bodily disturbances” are conventionally considered byproducts or expressions of the so-called standard emotions — “surprise, curiosity, rapture, fear, anger, lust, greed, and the like” — these corporeal reverberations are actually the raw material of the emotion itself.” I tend to agree with him. Maria Popova writes beautifully and insightfully about his essay here.

The releases of adrenaline that we experience when we are afraid or nervous, of cortisol when we are anxious or stressed, of dopamine when we are happy and thrilled, of oxytocin when we feel loved and cared for are all manifestations of the body responding automatically to what is going on around us. When we learn to look for it and recognise it, it is great data that our bodies are providing us with.

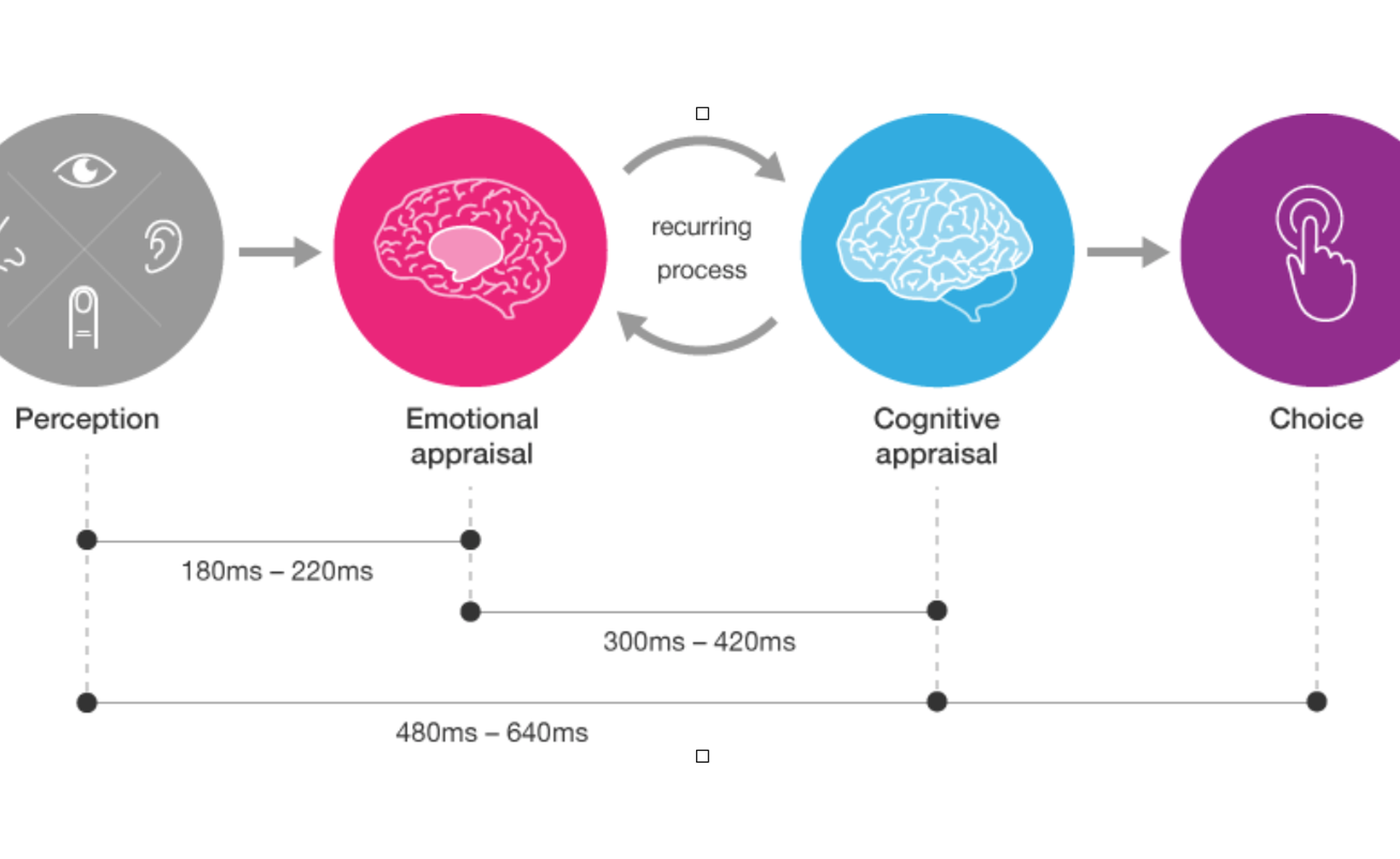

Another thing that happens is that within micro seconds of experiencing that somatic response, we give meaning to it, as demonstrated in the illustration accompanying this article.

Within 300 - 420 milliseconds we have cognitively given an explanation to what we are feeling. Emphasis on the ‘we’ - not someone else. It is our explanation, our stuff. “He doesn’t like me’, "She is annoyed with me” ‘This isn’t going well” ‘They shouldn’t be doing that” “this is outrageous” “I hate this” “I hate them” and so on.

So, could argue that the following equation could be true

Bodily Response + Our Explanation = Emotion.

Anger + “This should be working properly” = Frustration

Happiness + “these people like my jokes” = Satisfaction

Sadness + “My friend hasn’t returned my call” = Disappointment

Fear + “They know more than me and I look stupid” = Anxiety

Shock + “I have been wronged by that person’ = Hurt

It is when we begin to be able to parse out our emotions - to analyse something, as a speech or behaviour, to discover its implications or uncover a deeper meaning - that we really begin to be intelligent about it and to do something with it. We can begin to change the thoughts that we habitually turn to and experiment with replacing them with others. We can intervene with ourselves physiologically and behaviourally. We can go for a run to disperse cortisol, the stress hormone. We can count to three, take some deep breaths and go for a short walk when the pulse of anger surges through our bodies. When your hotel room key doesn’t work, you can tell yourself ‘Getting annoyed isn’t helping me”, notice the little buzz of adrenaline in your throat and begin the weary trudge back to the lift. (elevator.)

John Hill is a Systems and Team Coach, Leadership Coach, AoEC Faculty Team Coaching and AoEC Consultant Coach.

Article

1st December 2025 by Lee Robertson

If there’s one thing the latest Global Culture Report from the O.C. Tanner Institute makes clear, it’s this: workplace culture…

News

13th November 2025 by Lee Robertson

We’re pleased to announce that the AoEC’s Mentor Coaching and Group Supervision programmes are now available for bookings in 2026.

Article

18th November 2025 by Lee Robertson

Most organisations say they’re “team-based” - but how well do they understand the teams that drive their business forward?